Something we repeatedly do daily create our habit. These habits, or patterns make our life easier: imagine having to think which corner of your mouth to start brushing your teeth in every morning?

Patterns definitely save our brains for more meaningful decision makings. However, we may sometimes need to reevaluate these patterns and leave some behind.

Takahiro Kondo, internationally renowned contemporary ceramic artist, has done at least two major pattern breakings in his life which led to a milestone in his career… It’s not the way he brushes his teeth, in case you’re wondering!

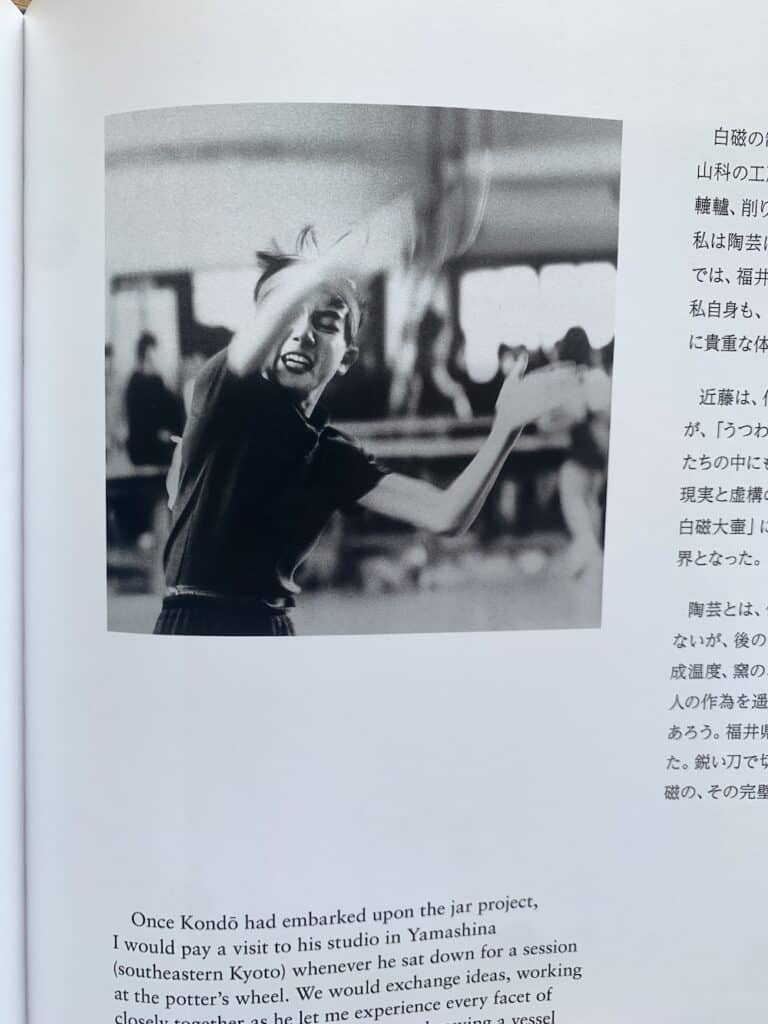

As a high school table tennis player, he won a national championship. It was when he entered University that he stopped winning. He couldn’t win the national league and didn’t understand why.

The first year, and the second year, he still couldn’t win. There was no one to tell him how to improve so all he could do was to keep going at it.

“I don’t know how I graduated from the university because I spent 12 hours practising every day,” he now laughs.

From that practice, though, something was starting to manifest. He realised what he had learnt in his high school time was the pattern to win a high school tournament. He perfectly fitted himself into the mould. But at the university and for the world-level competition, he had to break out of it. And he had to do it by himself.

To me, breaking my own pattern by myself seems hard: I have to objectively observe what is not working and find ways to fix it. It must be so much easier if someone else told me.

Kondo didn’t have a coach to teach him how to break the mould, so he spent two years searching in the dark. In his third year, he started seeing a ray of light: in a newly discovered realm, he was able to tap into his non-thinking state while harmoniously filled with his energy and intention to win.

Another pattern-breaking came almost a decade after. By that time, he had decided to pursue his family lineage of ceramic art. His grandfather was recognised as a Living National Treasure for the mastery of blue underglaze on white jars or round plates, and his father Hiroshi was also a master of the craft. He apprenticed under his father with the intention to master the craft.

It was when he was invited to Sao Paolo, Brazil, to exhibit his works that his first encounter with the world of contemporary art happened.

“At that time, there was no space for crafts in contemporary art. Objects of utilitarian nature are ranked below ‘fine art’. In table tennis, I could go play at the world level if I was good enough. But in the world of art, there was no way for me to compete on the same stage with other artists.”

“I had nothing to prove then. I hadn’t even started on my artistic journey, but I was seriously contemplating how to compete with the rest of the world.” He said it like a joke, but I sensed it to be true.

So he stopped making jars, bowls or plates; nothing made with the purpose for use. He started experimenting with drawing and creating objects that are not thrown on wheels. He had to unlearn everything he had taken for granted in ceramics, the way he had been taught by his father and grandfather.

During the unlearning process, Kondo discovered new techniques, materials, and expressions of his art that had never been done by anyone else.

There was also an unexpected fruit of unlearning. When he came back to a potter’s wheel after a long halt, his father saw his work and said, “you became much better at this.”

The complete disassociation enabled him to forget the pattern he used to hold onto.

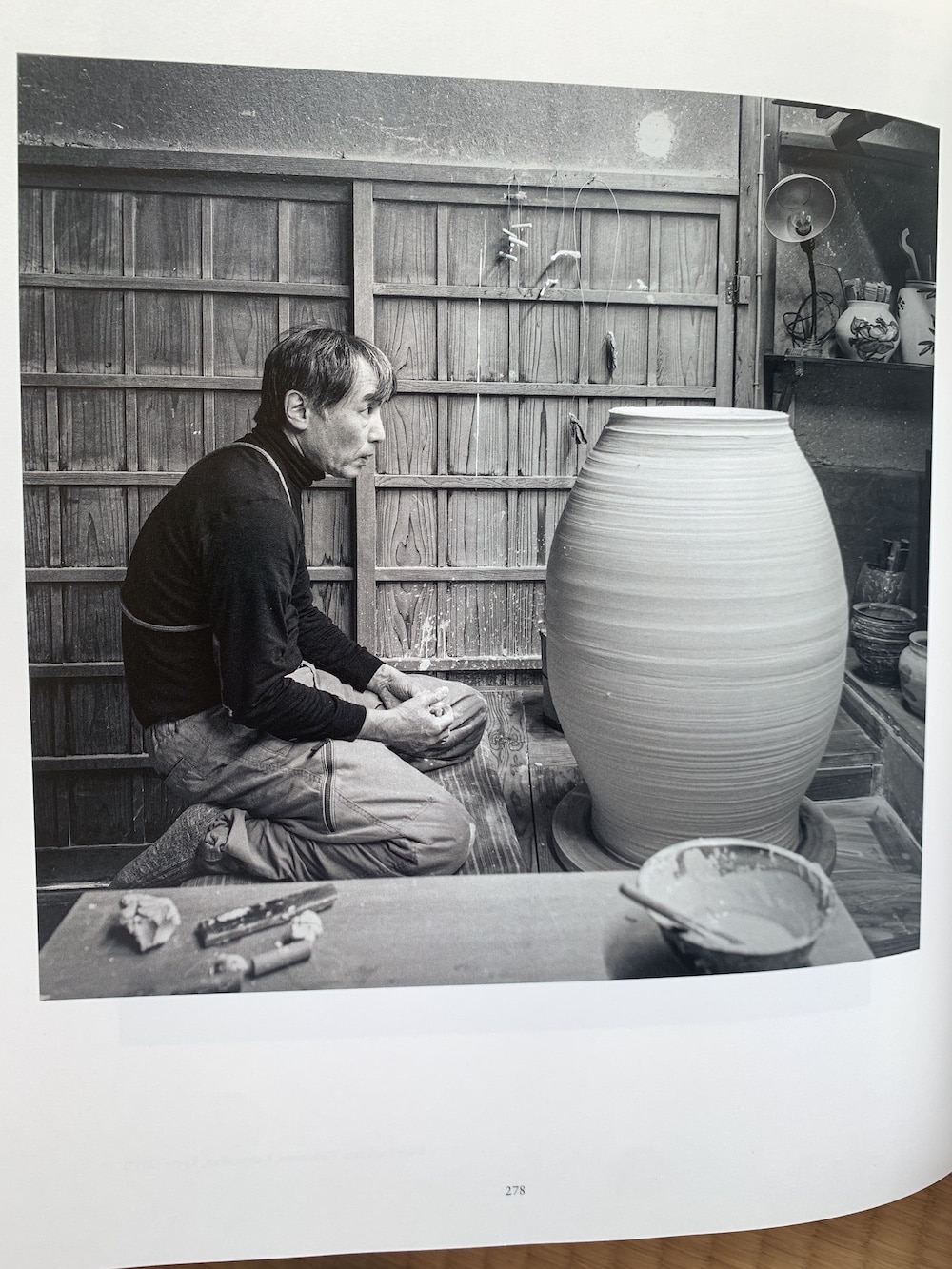

Lately, he is faced with a ginormous moon jar on his wheel.

Purchase his photobook

0 Comments